Growing Community Conservation, Part II

(This article is adapted from Angela’s presentation at SJPT’s Annual Meeting on May 5. Part two of a two-part series. See Part I here.)

Over the past decades as the land trust movement has matured, it has gone through various evolutionary stages. The first is land acquisition; the second is an emphasis on stewardship and adoption of organizational standards of practice; and the third stage is community conservation. These three stages normally overlap in time and are not at all mutually exclusive.

Stage One

This first evolutionary stage was an understandable movement and reaction to counter the onslaught of lands disappearing to development.

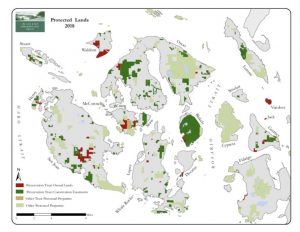

The San Juan Preservation Trust was founded in 1979, almost 40 years ago. Today, as a result of the Preservation Trust and our wonderful partners—including you—there are more than 60 preserves in the islands and over 18,000 conserved acres (an area about the size of Lopez Island). Most of this conserved land consists of privately owned parcels on which we hold conservation easements. These are scattered across 20 islands in the San Juan archipelago. The Preservation Trust has been enormously productive in its ongoing acquisition phase.

Stage Two

During the second evolutionary stage, the emphasis begins to shift toward stewardship—that is, taking care of the land acquired in phase one—and on developing standards and practices.

The Land Trust Alliance demonstrated great leadership in the aftermath of controversy surrounding some national land trusts by creating and incorporating the Land Trust Accreditation Commission in April 2006 as an independent program of the Land Trust Alliance.

The mission of the Land Trust Accreditation Commission is to inspire excellence, promote public trust and ensure permanence in the conservation of open lands by recognizing land trust organizations that meet rigorous quality standards and that strive for continuous improvement.

The mission of the Land Trust Accreditation Commission is to inspire excellence, promote public trust and ensure permanence in the conservation of open lands by recognizing land trust organizations that meet rigorous quality standards and that strive for continuous improvement.

The Preservation Trust has successfully gone through the accreditation process, first in 2012 and then renewing its 5-year term of accredited status last year. There are now about 400 accredited land trusts (out of a total of more than 1,400 land trusts) in the United States. Each accredited land trust is stronger as a result of meeting the accreditation commission’s stringent standards of excellence, and this has contributed to a far stronger land trust movement nationwide.

What this all means is that we all have good systems and practices in place to ensure we will be around to deliver on our promise of protecting important conservation lands in perpetuity.

Stage Three

While the land trust movement was focused on strengthening our stewardship and organizational systems, a clarion call has emerged for land trusts and our nation as a whole.

This 2005 book sounded a clarion call.

This clarion call came in the form of Richard Louv’s influential and national bestseller book, Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder – which is about the growing divide between children and the outdoors. Louv directly linked the lack of nature in the lives of today’s wired generation to some of the most disturbing childhood trends, such as rises in obesity, attention disorders, and depression.

Last Child in the Woods was the first book to bring together a growing body of research indicating that direct exposure to nature is essential for healthy childhood development and for the physical and emotional health of children and adults.

For land conservationists, this book was a serious warning about our culture shifting further and further away from the land and nature.

You see a common thread among our nation’s great conservationists (Thoreau, Muir, Leopold, etc.) — regular quiet and contemplative time in nature leading to great realizations, healing and love for nature. In other words, those quiet times in nature were the transformative experiences that helped form those great people.

Our challenge is to inspire kids to put down their devices and to venture outdoors. Without a deep and direct connection with nature, the key ingredient for good stewardship of the Earth is missing: love. These island communities share values and traditions, as well as a love of nature flowing from regular quiet and contemplative time in nature.

The next evolutionary stage of the land trust movement must include greater emphasis on providing more people—specifically children—with the ability to directly and deeply connect with nature. With this deep connection, these islanders can become great lovers, and thus strong stewards, of our islands and our planet.

Community Conservation: It’s the right and smart thing to do

The Land Trust Alliance recently highlighted studies showing that the most direct route to caring for the environment as an adult is participating in outdoor activities before the age of 11. Only if children engage with nature, learn about nature, and care about nature can we have a reasonable hope that they will grow into adults who will help protect forever the lands we protect now.

Engaging in outdoor activities before the age of 11 is the most direct route to caring for the environment as an adult.

A Stanford University review of over 100 studies examined the benefits of environmental education found that it improves academic performance, enhances critical thinking, develops confidence and leadership skills, and increases civic engagement and positive environmental behaviors.

By connecting more young people with the land, we could broaden support for land conservation and help make our communities better places in which to learn and live.

The Preservation Trust is doing this work with collaborative projects such as these:

| Project | Partners |

| Western Bluebird Reintroduction Project | American Bird Conservancy, Center for Natural Lands Management, Spring Street International School, Friday Harbor Elementary School, Orcas Island High School, San Juan County Land Bank, Cowichan Valley Naturalists, SJPT volunteers |

| Island Marble Butterfly Habitat Expansion Project | National Park Service, San Juan County Land Bank, US Fish & Wildlife, Bureau of Land Management, Spring Street International School, Waldorf School (Seattle), San Juan Iisland Youth Conservation Corps, Washington Conservation Corps, SJPT volunteers |

| Salish Seeds Project | San Juan County Land Bank, Center for Natural Lands Management, SJPT volunteers |

| Graham Preserve Trail Project | Nick Teague (US Bureau of Land Management), Sarah Hanson (formerly with the Washington Trails Association), American Hiking Society, San Juan Island Youth Conservation Corps, Lopez Island Youth Conservation Corps, Orcas Island Youth Conservation Corps, Shaw Island School, San Juan Preservation Trust staff and volunteers |

Orcas Island Youth Conservation Corps doing trail work on SJPT’s Graham Preserve, Summer 2016

Planning Ahead

Over the next year, our trustees and staff will be embarking on strategic planning for the Preservation Trust. We will be asking ourselves, and engaging with you, our members and supporters, as well as other stakeholders in our island communities, a list of questions to help us clarify our direction and goals for the future. I’ll be writing more about this initiative in coming issues, so stay tuned!