Ro Veidovi: What’s in a Name?

By Thyatira Thompson

Aerial view of Vendovi Island from the west | Staff Archive

America would not be what it is today if not for the people from all corners of the world and walks of life who share in its story and contribute to its rich diversity. I am glad that the diverse cultures that make up the America of today are both acknowledged and celebrated. May is Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, so I would like to take this opportunity to share the story of a Fijian ruler, Chief Ro Veidovi—or, as his captors would called him, “Vendovi”—whose name graces one of the islands here in the San Juans (along with the name Viti Rocks for a smaller island directly adjacent, Viti being the Indigenous name for Fiji.)

How is it that a Fijian chief found himself here in the Salish Sea in the first place, and why was an island named in his honor, an American tradition normally reserved for naval officers?

Ro Veidovi’s story is inextricably linked with the United States Exploring Expedition and the expedition’s commander, Charles Wilkes. The United States Exploring Expedition, or the “U.S. Ex. Ex.,” was America’s first attempt to launch a voyage of exploration into the Pacific and ranks as one of the most successful scientific expeditions of the nineteenth century. The enormous collection of natural history specimens and cultural artifacts collected on the expedition would eventually go on to become the founding collection of the Smithsonian Institution, while much of the west coast of North America was charted including dozens of islands and atolls.

But while the main objective of the U.S. Ex. Ex. was that of scientific exploration, one specific job Wilkes was tasked with was to sail to Fiji, apprehend Chief Veidovi, and bring him back to the U.S. for an incident involving the demise of the crew from an American whaling ship, the Charles Doggett. In the 1830s, Salem traders from New England found they could make good money by drying and selling bêche-de-mer, or sea cucumbers, slug-like marine animals that flourished in Fiji’s coral reefs. They were then shipped to Manila or directly to Canton where “the prized soup ingredient fetched handsome profits.” Veidovi was wanted for murder after being accused of masterminding the deaths of eleven men who were curing sea slugs on a Fijian beach in 1834.

One common practice of the bêche-de-mer traders was the temporary hostage–taking of chiefs in the course of trade negotiations. And while it is not entirely clear why Veidovi might have helped murder the men of the Charles Doggett, one theory is that the crew of the Doggett abused and mistreated one of the local chiefs whom they took as a temporary hostage, and who just so happened to have been a relative of Veidovi. When word of this abuse got back to Veidovi, he felt compelled to rescue his relative. The rescue was successful but would bring about a vengeful fury from the Expedition that would see villages destroyed and burned to the ground. Wilkes himself would eventually find himself court-martialed upon his return to the U.S. due to the over-the-top violence he employed. Veidovi himself, in hopes to end this violence against the Fijians, agreed to surrender and return with the expedition back to the U.S. Whether his retaliatory actions were justified would be settled at his trial, to be held in New York.

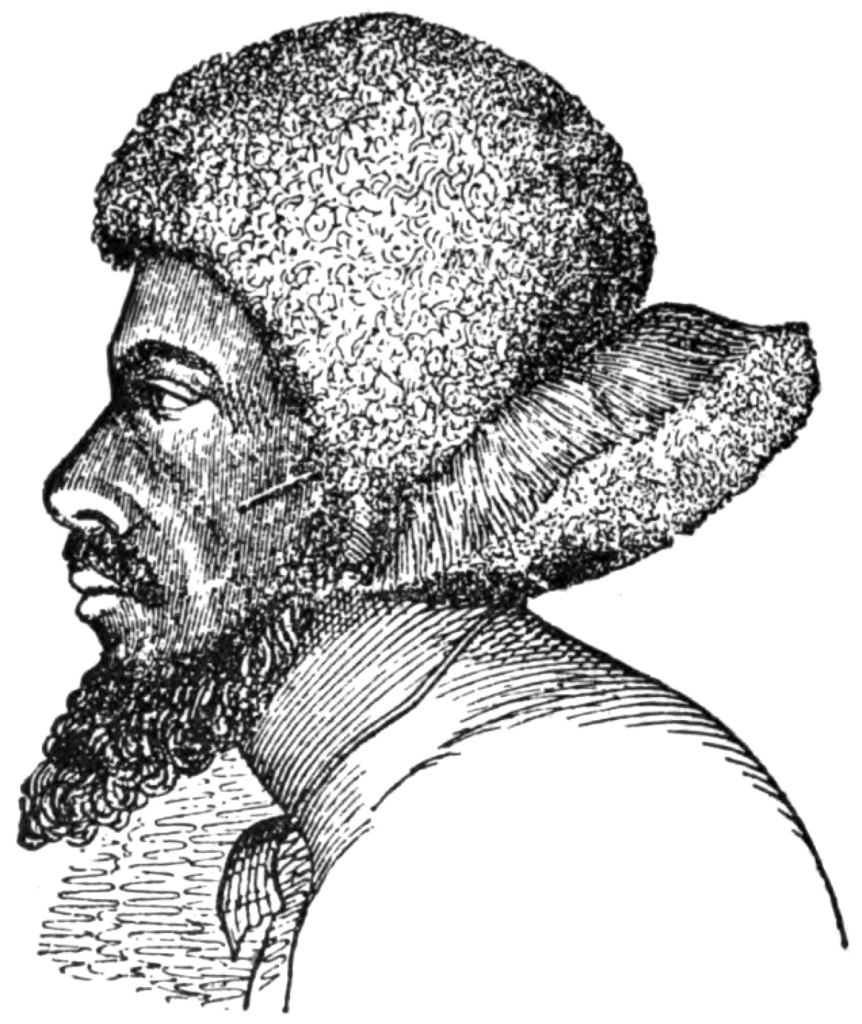

Drawing of Ro Veidovi by U.S. Exploring Expedition artist Alfred T. Agate| Courtesy American Historical Society

Sea cucumber (Holothuria perviax) | Photo by “Nemo’s great uncle” (CC 2.0)

Vendovi Island as seen from above in 1941 | U.S. Geological Survey

Vendovi Island shoreline | Kurt Thorsen

On the voyage back to the states, Wilkes and his crew treated Veidovi as both a prisoner and a spectacle initially, somewhat of a captured savage who required taming. Almost all accounts of Veidovi’s voyage back to America describe the forced shaving of Veidovi’s hair, emblematic of an involuntary transformation to “civility.” But as time aboard the ship passed, the crew’s sentiment towards Veidovi transformed, causing them to befriend him, give him free passage on the ship, and rename the islands in his honor. Seaman Charles Erskine provided an account, saying “Vendovi … who had been captured … through the treachery of one of his nephews, declared … he would club, roast, and eat the treacherous fellow. Six months afterwards the old chief had become [so] much civilized that the irons were taken off him. He appeared to be a very thoughtful, genial, and pleasant sort of man.” Wilkes himself acknowledges in his autobiography that “until now he had been kept in irons, and as all apprehensions were over as to his escape, I ordered him to be set free. He was a model of a man, very tall and erect and of a proud bearing.” He was beloved on the Vincennes, and this is the consensus as to how Vendovi Island and Viti Rock received their present names.

Vendovi Island is currently a nature preserve owned by the San Juan Preservation Trust. I have been most fortunate to serve as the island’s caretaker now for going on eight seasons. In learning Veidovi’s story, I have a broader understanding of the interplay between global, oceanic, and local scales of history and how events that happened hundreds of years ago can shape what we experience today.

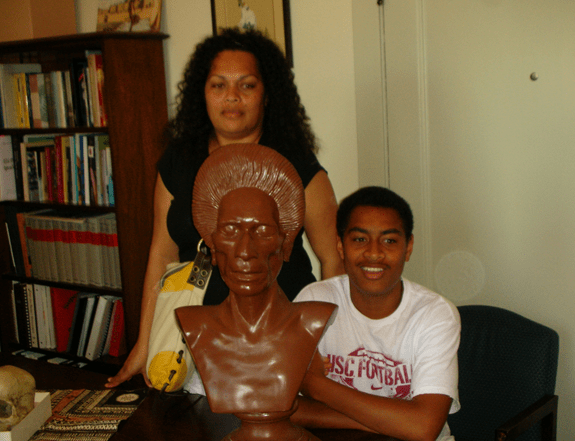

Veidovi never got the opportunity to testify in court. He would die June 10, 1842, the day the United States Exploring Expedition sailed into New York Harbor. His remains would be scattered and his skull put on display in Washington DC—first at the U.S. Patent Office and then transferred to the Division of Mammals in the newly built Smithsonian building in 1856. Since then and more recently, efforts have been made by his descendants and the Fijian government to share dialogue with the U.S. regarding Veidovi’s legacy and remains. Dr. Tony Adler in the Journal of Pacific History puts it this way:

The relic of the chief endures as a medium for Fijian and American efforts to renegotiate the memory of dignities and indignities sustained in the course of violent encounters on an oceanic frontier, while the displacement of one man, across a vast expanse of ocean continues, even today, to connect disparate parts of a Pacific World.

To that, I say, right on!

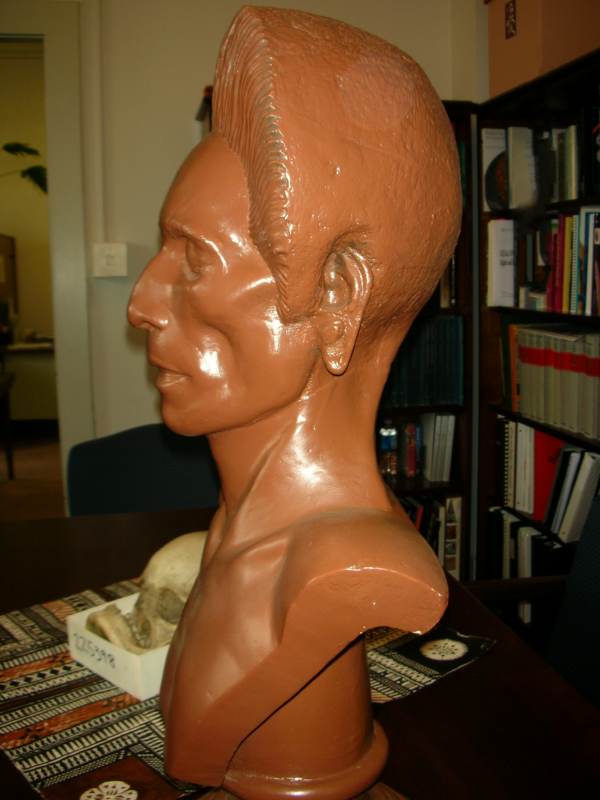

Bust and skull of Ro Veidovi | Terry Lindell

(I would be remiss if, in sharing this story, I did not acknowledge that the name Vendovi Island is only the most recent post-colonialist name given to this island. Renowned poet Rena Priest wrote a poem titled “Creation Story” that tells how the island we now call Vendovi got its name according to Lummi tradition.)

To learn more about Chief Veidovi, the history of Vendovi Island, and to visit a place with a complex cultural history that may urge us to ponder our own place in this increasingly global world, we invite you to visit SJPT’s Vendovi Island Preserve. We hope this account inspires you to forge more intercultural connections and to find a moment to celebrate and uplift Asian American and Pacific Islander heritage.

Descendants of Ro Veidovi with museum artifacts | Terry Lindell